Page103

Process Isolation

Process isolation is a logical control that attempts to prevent one process from interfering with another. This is a common feature among multiuser operating systems such as Linux, UNIX, or recent Microsoft Windows operating systems. Older operating systems such as MS-DOS provide no process isolation. A lack of process isolation means a crash in any MS-DOS application could crash the entire system. If you are shopping online and enter your credit card number to buy a book, that number will exist in plaintext in memory (for at least a short period of time). Process isolation means that another process on the same computer cannot interfere with yours.

Interference includes attacks on the confidentiality (reading your credit card number), integrity (changing your credit card number), and availability (interfering with or stopping the purchase of the book).

Techniques used to provide process isolation include virtual memory (discussed in the next section), object encapsulation, and time multiplexing. Object encapsulation treats a process as a “black box,” which we will discuss in Chapter 9, Domain 8: Software Development Security. Time multiplexing shares (multiplexes) system resources between multiple processes, each with a dedicated slice of time.

Hardware Segmentation

Hardware segmentation takes process isolation one step further by mapping processes to specific memory locations. This provides more security than (logical) process isolation alone.

Virtual Memory

Virtual memory provides virtual address mapping between applications and hardware memory. Virtual memory provides many functions, including multitasking (multiple tasks executing at once on one CPU), allowing multiple processes to access the same shared library in memory, swapping, and others.

Exam Warning

Virtual memory allows swapping, but virtual memory has other capabilities. In other words, virtual memory does not equal swapping.

Swapping and Paging

Swapping uses virtual memory to copy contents in primary memory (RAM) to or from secondary memory (not directly addressable by the CPU, on disk). Swap space is often a dedicated disk partition that is used to extend the amount of available memory. If the kernel attempts to access a page (a fixed-length block of memory) stored in swap space, a page fault occurs (an error that means the page is not located in RAM), and the page is “swapped” from disk to RAM.

Note

The terms “swapping” and “paging” are often used interchangeably, but there is a slight difference: paging copies a block of memory to or from disk, while swapping copies an entire process to or from disk. This book uses the term “swapping.”

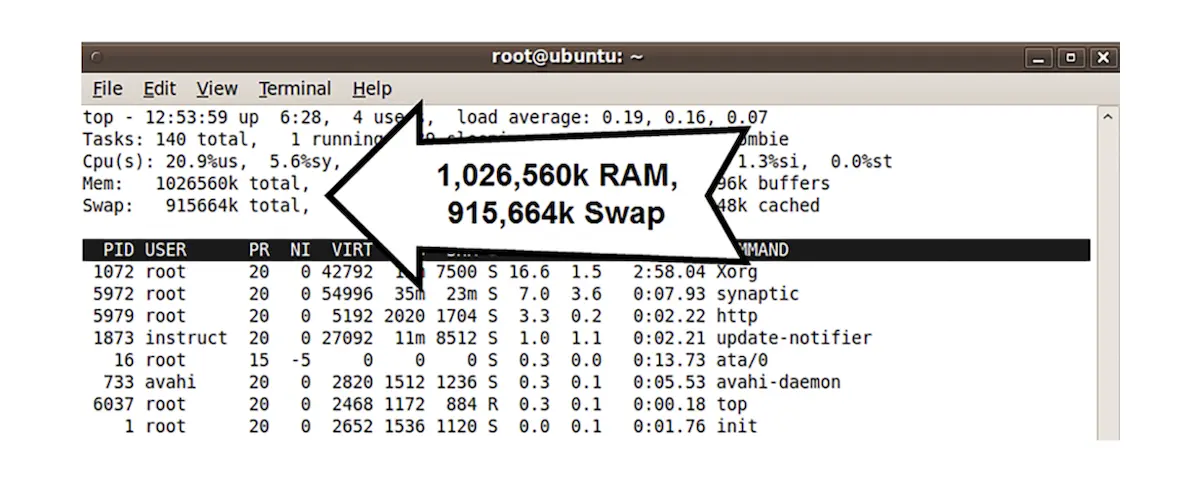

Fig. 4.11 shows the output of the Linux command “top,” which displays memory information about the top processes, as well as a summary of available remaining memory. It shows a system with 1,026,560 kb of RAM, and 915,664 kb of virtual memory (swap). The system has 1,942,224 kb total memory, but just over half may be directly accessed.

The output of the Linux command “top.”

The output of the Linux command “top.”

Most computers configured with virtual memory, as the system in Fig. 4.11, will use only RAM until the RAM is nearly or fully filled. The system will then swap processes to virtual memory. It will attempt to find idle processes so that the impact of swapping will be minimal.

Eventually, as additional processes are started and memory continues to fill, both RAM and swap will fill. After the system runs out of idle processes to swap, it may be forced to swap active processes. The system may begin “thrashing,” spending large amounts of time copying data to and from swap space, seriously impacting availability.

Swap is designed as a protective measure to handle occasional bursts of memory usage. Systems should not routinely use large amounts of swap: in that case, physical memory should be added, or processes should be removed, moved to another system, or shortened.