Page151

Lock Picking

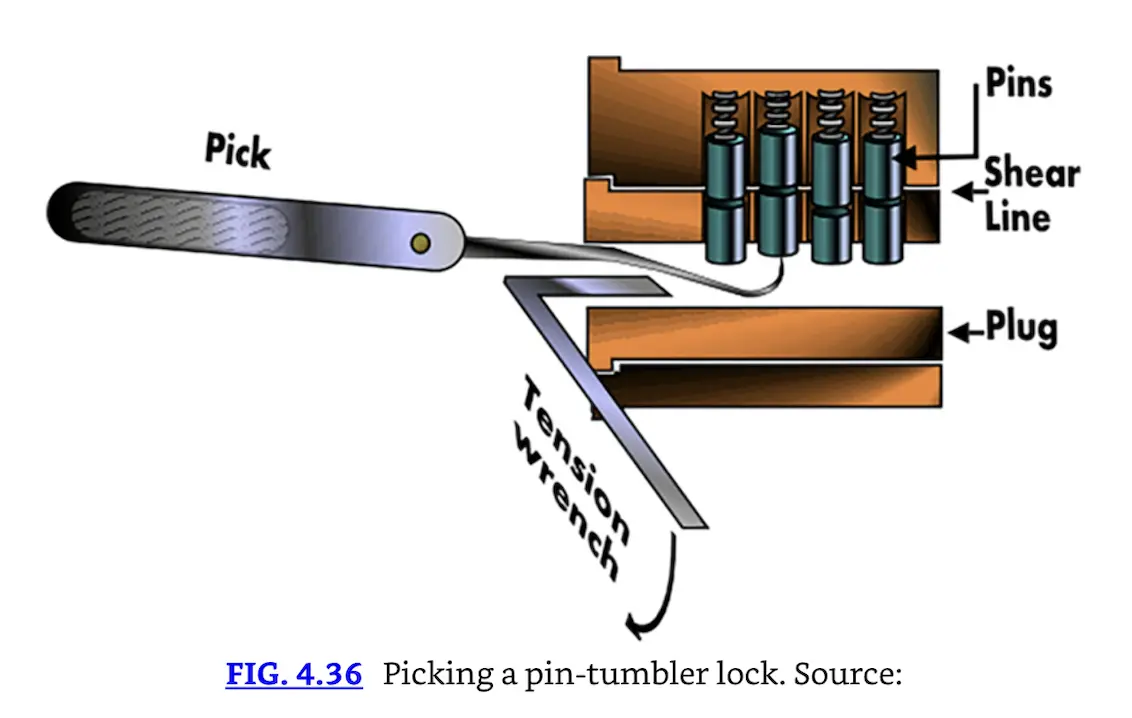

Lock picking is the art of opening a lock without a key. A set of lock picks, shown in Fig. 4.36, can be used to lift the pins in a pin tumbler lock, allowing the attacker to open the lock without a key. A newer technique called lock bumping uses a shaved-down key that will physically fit into the lock. The attacker inserts the shaved key and “bumps” the exposed portion (sometimes with the handle of a screwdriver). This causes the pins to jump, and the attacker quickly turns the key and opens the lock.

Fig. 4.36 Picking a pin-tumbler lock. Source: Wikimedia Commons; Drawn by Teresa Knott. Image under permission of Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 3.0.

All key locks can be picked or bumped; the only question is how long it will take. Higher-end locks will typically take longer to pick or bump. A risk analysis will determine the proper type of lock to use, and this “attack time” of a lock should be considered as part of the defense-in-depth strategy.

Master and Core Keys

The master key opens any lock for a given security zone in a building. Access to the master key should be tightly controlled, including the physical security of the key itself, authorization granted to a few critical employees, and accountability whenever the key is used.

The core key is used to remove the lock core in interchangeable core locks (where the lock core may be easily removed and replaced with another core). Once the lock core is removed, the door may often be opened with a screwdriver (in other words, the core key can open any door). Since the core key is a functional equivalent to the master key, it should be kept equally secure.

Combination Locks

Combination locks have dials that must be turned to specific numbers, in a specific order (alternating clockwise and counterclockwise turns) to unlock. Simple combination locks are often used for informal security, like your gym locker. They are a weak form of physical access control for production environments such as data centers. Button or keypad locks also use numeric combinations.

Limited accountability due to shared combinations is the primary security issue concerning these types of locks. Button or keypad locks are also vulnerable because prolonged use can cause wear on the most used buttons or keys. This could allow an attacker to infer numbers used in the combination. Also, combinations may be discovered via a brute-force attack, where every possible

combination is attempted. These locks may also be compromised via shoulder surfing, where the attacker sees the combination as it is entered.

Learn by Example

Hacking Pushbutton Locks

2600 Magazine, The Hacker Quarterly discussed methods for attacking Simplex locks (article also available online at http://fringe.davesource.com/Fringe/QuasiLegal/Simplex_Lockpicking.txt).

A common model of Simplex pushbutton lock in use at the time had five buttons (numbered one through five). The buttons must be pressed in a specific combination in order to open. This type of lock typically used only one of 1081 different combinations. The authors point out that a Master Lock used for high school gym lockers has 64,000 combinations: the dial represents numbers 1–40 and must be turned three times (40 × 40 × 40 = 64,000).

The authors were able to quickly determine the combination of a number of these locks via brute-force attacks. They discovered the combination used on drop boxes owned by a national shipping company, and then discovered the same combination opened every drop box on the east coast. They guessed the combination for another company’s drop boxes in one shot: the company never changed the default combination.

Simple locks such as pushbutton locks with limited combinations do not qualify as preventive devices: they do little more than deter an educated attacker. These locks can be used for low-security applications such as locking an employee restroom, but should not be used to protect sensitive data or assets.