Page216

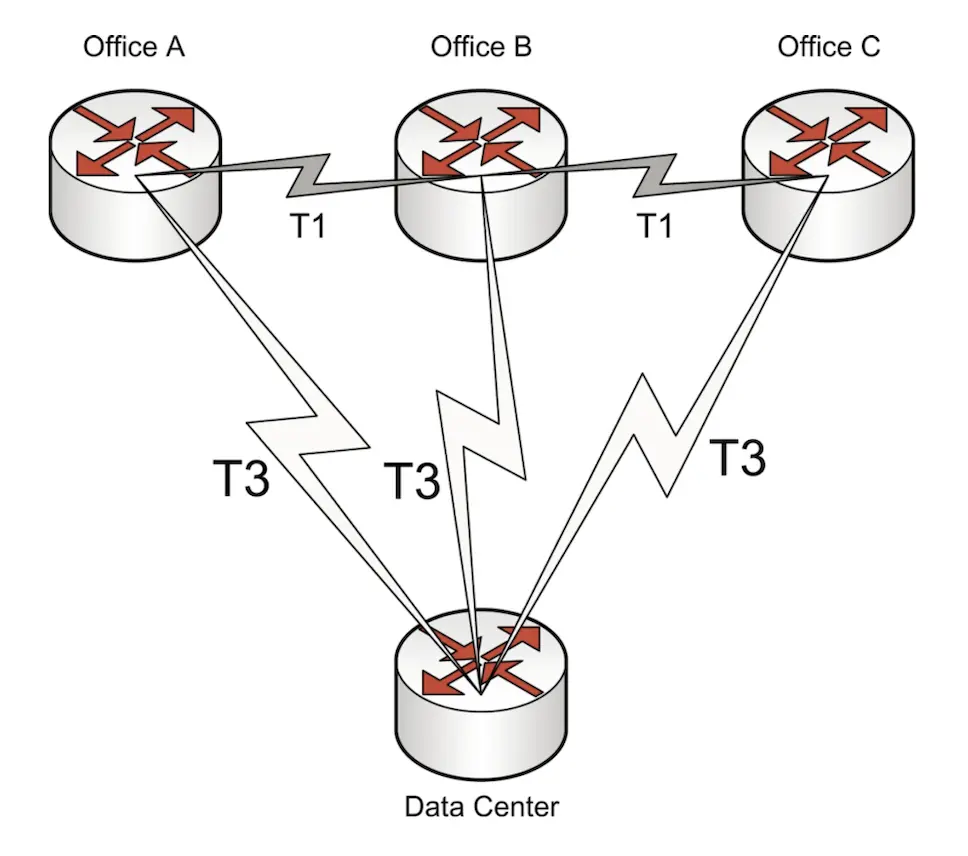

Should the left-most T3 circuit go down, between the data center and Office A, there are multiple paths available from the data center to Office A: the fastest is the T3 to Office B, and then the T1 to Office A.

You could use static routes for this network, preferring the faster T3s over the slower T1s. The problem: what happens if a T3 goes down? Network engineers like to say that all circuits go down eventually. Static routes would require manual reconfiguration.

Routing protocols are the answer. The goals of routing protocols are to automatically learn a network topology and learn the best routes between all network points. Should the best route go down, backup routes should be chosen, and chosen quickly. And ideally this should happen even while the network engineers are asleep.

Convergence means that all routers on a network agree on the state of routing. A network that has had no recent outages is normally “converged”: all routers see all routes as available. Then a circuit goes down. The routers closest to the outage will know right away; routers that are further away will not. The network now lacks convergence: some routers believe all circuits are up, while others know one is down. A goal of routing protocols is to make convergence time as fast as possible.

Routing protocols come in two basic varieties: Interior Gateway Protocols (IGPs), like RIP and OSPF, and Exterior Gateway Protocols (EGPs), like BGP. Private networks like Intranets use IGPs, and EGPs are used on public networks like the Internet. Routing protocols support Layer 3 (Network) of the OSI model.

Distance Vector Routing Protocols

Metrics are used to determine the “best” route across a network. The simplest metric is hop count. In  , the hop count from the data center to each office via T3 is 1. Additional paths are available from the data center to each office, such as the T3 to Office B, followed by the T1 to Office A.

, the hop count from the data center to each office via T3 is 1. Additional paths are available from the data center to each office, such as the T3 to Office B, followed by the T1 to Office A.

The latter route is two hops, and the second hop is via a slower T1. Any network engineer would prefer the single-hop T3 connection from the data center to Office A, instead of the two-hop detour via Office B to Office A. And all routing protocols would do the same, choosing the one-hop T3.

Things get trickier when you consider connections between the offices. How should traffic route from Office A to B? The shortest hop count is via the direct T1. But that link only has 1.5 megabits: taking the two-hop route from Office A down to the data center and back up to Office B offers 45 megabits, at the expense of an extra hop.

A distance vector routing protocol such as RIP would choose the direct T1 connection and consider one hop at 1.5 megabits “faster” than two hops at 45 megabits. Most Network Engineers (and all Link state routing protocols, as described in the next section) would disagree.

Distance vector routing protocols use simple metrics such as hop count, and are prone to routing loops, where packets loop between two routers. The following output is a Linux traceroute of a routing loop, starting between hops 16 and 17. The nyc and bos core routers will keep forwarding the packets back and forth between each other, each believing the other has the correct route.

14 pwm-core-03.inet.example.com (10.11.37.141) 165.484 ms 164.335 ms 175.928 ms

15 pwm-core-02.inet.example.com (10.11.23.9) 162.291 ms 172.713 ms 171.532 ms

16 nyc-core-01.inet.example.com (10.11.5.101) 212.967 ms

17 bos-core-01.inet.example.com (10.11.5.103) 206.296 ms

193.454 ms 199.457 ms

18 nyc-core-01.inet.example.com (10.11.5.101) 210.201 ms

225.674 ms 208.124 ms

19 bos-core-01.inet.example.com (10.11.5.103) 189.089 ms

201.505 ms 201.659 ms

20 nyc-core-01.inet.example.com (10.11.5.101) 334.19 ms 320.39 ms

245.182 ms

21 bos-core-01.inet.example.com (10.11.5.103) 218.519 ms

210.519 ms 246.635 ms