Page250

Kerberos Strengths

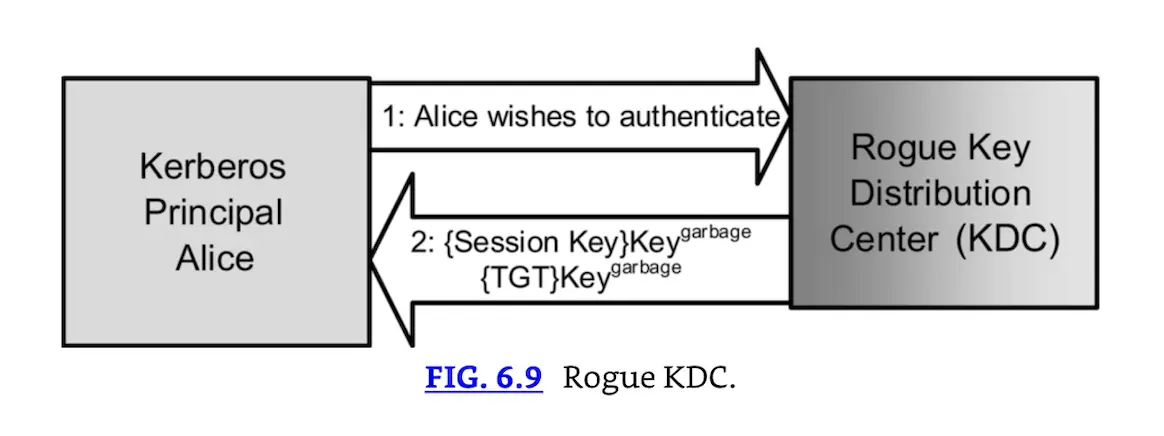

Kerberos provides mutual authentication of client and server. We have seen how the TGS and server (such as a printer) know that Principal Alice is authenticated. Alice also knows that the KDC is the real KDC. The real KDC knows both Alice’s and the TGS’s keys. If a rogue KDC pretended to be a real KDC, it would not have access to those keys. Fig. 6.9 shows steps 1 and 2 of Alice attempting to authenticate via a rogue KDC.

Rogue KDC.

Rogue KDC.

The rogue KDC does not know Alice’s or the TGT’s keys. So it supplies garbage keys (“KeyGarbage”). When Alice tries to decrypt the session key, she will get garbage, not a valid session key. Alice will then know the KDC is bogus.

Kerberos mitigates replay attacks (where attackers sniff Kerberos credentials and replay them on the network) via the use of timestamps. Authenticators contain a timestamp, and the requested service will reject any authenticator that is too old (typically 5 minutes). Clocks on systems using Kerberos need to be synchronized for this reason: clock skew can invalidate authenticators.

In addition to mutual authentication, Kerberos is stateless: any credentials issued by the KDC or TGS are good for the credential’s lifetime, even if the KDC or TGS goes down.

Kerberos Weaknesses

The primary weakness of Kerberos is that the KDC stores the keys of all principals (clients and servers). A compromise of the KDC (physical or electronic) can lead to the compromise of every key in the Kerberos realm.

The KDC and TGS are also single points of failure: if they go down, no new credentials can be issued. Existing credentials may be used, but new authentication and service authorization will stop.

Replay attacks are still possible for the lifetime of the authenticator. An attacker could sniff an authenticator, launch a denial-of-service attack against the client, and then assume or spoof the client’s IP address.

In Kerberos 4, any user may request a session key for another user. So Eve may say, “Hi, I’m Alice and I want to authenticate.” The KDC would then send Eve a TGT and a session key encrypted with Alice’s key. Eve could then launch a local password-guessing attack on the encrypted session key, attempting to guess Alice’s key. Kerberos 5 added an extra step to mitigate this attack: in step 1 in Fig. 6.8, Alice encrypts the current time with her key and sends that to the KDC. The KDC knows Alice is authentic (possesses her key), and then proceeds to step 2.

Finally, Kerberos is designed to mitigate a malicious network: a sniffer will provide little or no value. Kerberos does not mitigate a malicious local host: plaintext keys may exist in memory or cache. A malicious local user or process may be able to steal locally cached credentials.

Kerberos Exploitation

Kerberos being a primary credential gatekeeper in many enterprise environments means that attacks against this ecosystem are ubiquitous and should be expected. The most common attack against Kerberos involves adversaries simply gaining access to and impersonating already authenticated security principals. Strictly speaking, this does not truly involve exploitation of Kerberos, but rather simply the leveraging of an account’s previously issued service tickets. Within the Kerberos ecosystem, leveraging a user’s currently validated service ticket would allow the adversary access to resources already being accessed by the user.

More overtly Kerberos-centric attack patterns also exist. MITRE’s ATT&CK® Enterprise Matrix includes Technique 1558 (T1558): Steal or Forge Kerberos Tickets, which additionally highlights specific attack patterns such as Golden Ticket, Silver Ticket, and Kerberoasting [13]. In each case, the overarching goal is for the adversary to undermine Kerberos authentication to present as a legitimate user, which can enable the adversary’s lateral movement and allow general access throughout the victim environment.